Two exams over. Two more due on Thursday. One next week Monday. An interview and volunteer thing this week.

Find a happy place. Find a happy place. Find a happy place...

...ooh, glowy! :D

That cute little beach scene was done entirely in glowing bacteria, probably Escherichia coli. These particular bacteria glow only under blacklight, but is is possible to make bacteria really glow in the dark as well. Since I have actually done this process, I know a few things about how they make bacteria glow in any color you choose.

First, you need to isolate the gene that makes the protein you want. Most blacklight-sensitive bacteria will be using jellyfish ( Aequorea victoria) genes. Some pigments, like the red up there, probably came from an anemone that glowed red in its lifetime. There are even genes isolated from protists that really do glow in the dark! There are special enzymes out there that cut DNA strands at certain sequences, and you need to find the right tool to cut out the ones that glow in the dark. We did not do this in class, but what we did do was pretty cool.

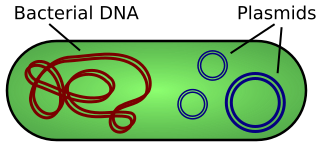

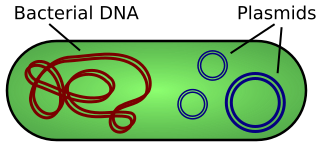

After being isolated, the glowing gene is integrated into something called a plasmid ring. Bacteria aren't like more complex organisms in that their DNA is fixed; instead, they are constantly recombining DNA from their environment and from each other! There was a whole temperature-changing process (I recall ice being involved) to make sure the bacteria took their extra DNA.

Also on the plasmid ring was an antibiotic; this ensured that only the bacteria with the glowing plasmid ring survived and multiplied. We needed a lot of them, after all. We selected the glowing ones out by putting smears on petri dishes laced with antibiotics. This is also how scientists test for antibiotic resistance in bacteria. If they can survive on that plate, watch out!

We had to wait a bit for the bacteria to grow, but after that, we put them under blacklight and practiced painting with them. Yes, painting. With brushes. There were no special scientific tools involved with drawing on a petri dish. By the end, we had a few good practice cultures of bacteria that glowed green under blacklight - just like Alba and GloFish!

Finally, after getting a good, pre-made culture of glowing bacteria, we took out paintbrushes...and just started painting on petri dishes. This has been done with other organisms since at least Alexander Fleming (the guy who discovered penicillin) using E.coli and other microbes, including fungi. We've been painting with germs for a while, and here's the end result:

Find a happy place. Find a happy place. Find a happy place...

...ooh, glowy! :D

That cute little beach scene was done entirely in glowing bacteria, probably Escherichia coli. These particular bacteria glow only under blacklight, but is is possible to make bacteria really glow in the dark as well. Since I have actually done this process, I know a few things about how they make bacteria glow in any color you choose.

First, you need to isolate the gene that makes the protein you want. Most blacklight-sensitive bacteria will be using jellyfish ( Aequorea victoria) genes. Some pigments, like the red up there, probably came from an anemone that glowed red in its lifetime. There are even genes isolated from protists that really do glow in the dark! There are special enzymes out there that cut DNA strands at certain sequences, and you need to find the right tool to cut out the ones that glow in the dark. We did not do this in class, but what we did do was pretty cool.

After being isolated, the glowing gene is integrated into something called a plasmid ring. Bacteria aren't like more complex organisms in that their DNA is fixed; instead, they are constantly recombining DNA from their environment and from each other! There was a whole temperature-changing process (I recall ice being involved) to make sure the bacteria took their extra DNA.

Also on the plasmid ring was an antibiotic; this ensured that only the bacteria with the glowing plasmid ring survived and multiplied. We needed a lot of them, after all. We selected the glowing ones out by putting smears on petri dishes laced with antibiotics. This is also how scientists test for antibiotic resistance in bacteria. If they can survive on that plate, watch out!

We had to wait a bit for the bacteria to grow, but after that, we put them under blacklight and practiced painting with them. Yes, painting. With brushes. There were no special scientific tools involved with drawing on a petri dish. By the end, we had a few good practice cultures of bacteria that glowed green under blacklight - just like Alba and GloFish!

Finally, after getting a good, pre-made culture of glowing bacteria, we took out paintbrushes...and just started painting on petri dishes. This has been done with other organisms since at least Alexander Fleming (the guy who discovered penicillin) using E.coli and other microbes, including fungi. We've been painting with germs for a while, and here's the end result:

|

| I look too sober for my own good. -.-; |